Relations between the Maldives and India have been mostly lukewarm since the election of Mohamed Muizzu as the former’s new President last September. Muizzu, who has ties to former Presidents Maumoon Abdul Gayoom and Abdulla Yameen, ran on a pro-China platform, defeating strongly pro-India candidate Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, backed by the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), the largest party in the country. After a period of relative post-electoral tranquillity and rapprochement, Muizzu now faces his first diplomatic crisis with New Delhi, sparked by disparaging comments made by Maldivian officials about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The crisis is particularly aggravated by Maldivian political culture, where foreign policy plays a strong role in a candidate’s profile, and even perceived allegiance to one camp - in Muizzu’s case, China - must be met with scepticism towards the other.

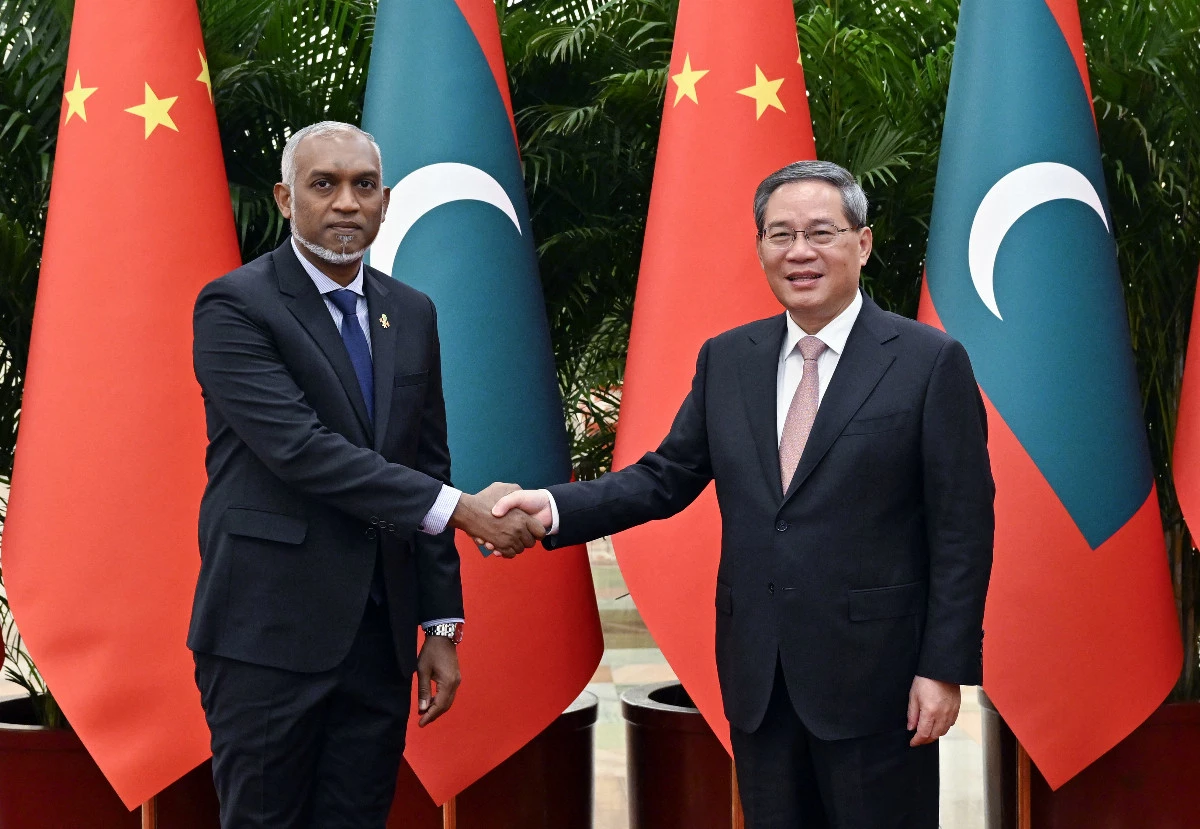

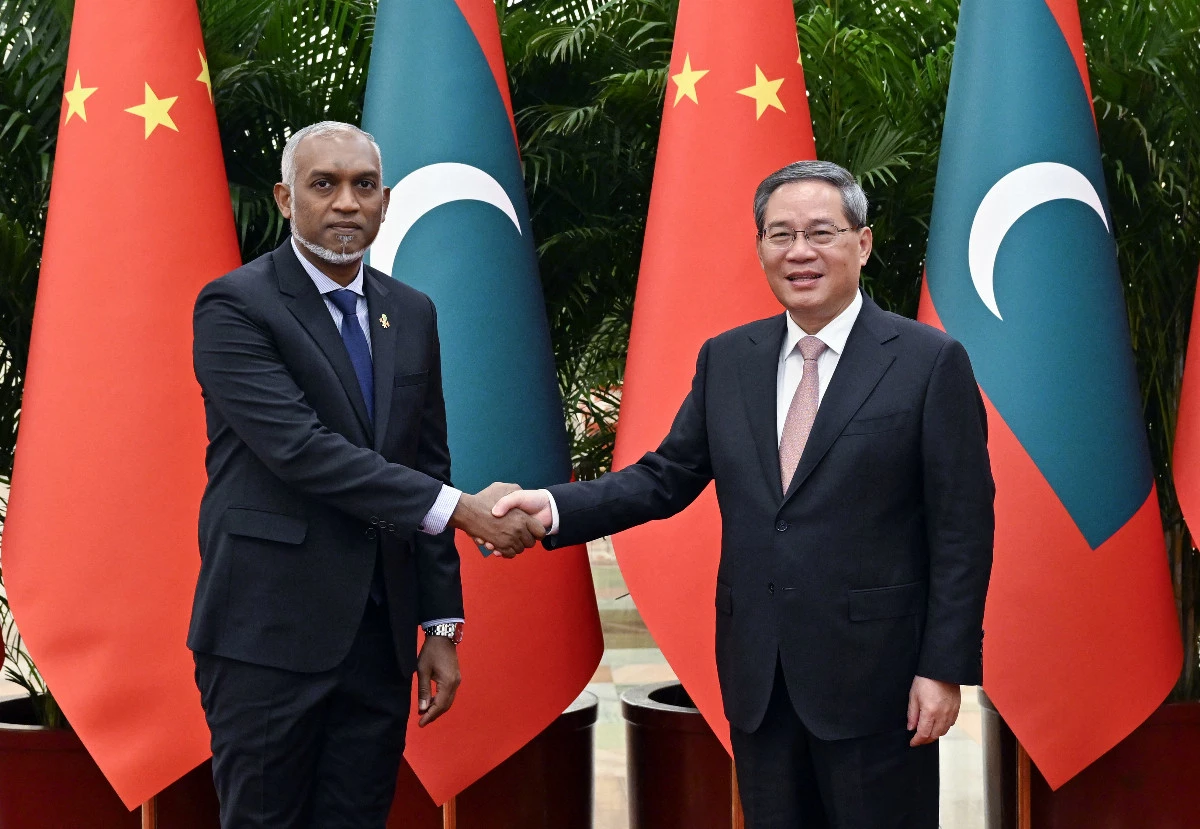

Since the end of Maumoon’s 30-year Presidency in 2008, the Maldivian political system has repeated a pattern common to States undergoing processes of democratisation. It is strongly polarised and highly unstable, with personal allegiances to a specific candidate weighing more than party or ideological preferences. Party ideologies are conditioned by their leaders, who also define the parties’ - and, eventually, governments’ - geopolitical orientation. Upon taking office, Muizzu had established a much more moderate profile on foreign policy than previously expected by Malé’s Western and Indian partners. The recent diplomatic spat, which coincided with a visit by the Maldivian President to Beijing, appears to have positioned him back into his original pro-China - or, at least, India-sceptic - position, calling for further engagement with the Chinese as an alternative to the damaged ties with New Delhi.

The Maldives, despite its relatively small area and population, are of high geostrategic importance in the Indian Ocean and, as such, geopolitical considerations play a major role in local politics. The archipelago’s proximity to India, integration in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and reduced military capacities give it an outsized role in the region. Under the previous pro-India administration, India established a naval base in the Maldivian atoll of Uthuru Thila Falhu, jointly administered with the Maldivian defence forces. The project was perceived as an encroachment of Maldivian sovereignty by the opposition, with Muizzu campaigning on an “India out” platform.

In the perennial Maldivian meandering between India and China, Europe appears as, at best, a distant player and, at worst, an aloof spectator. Brussels has traditionally been seen as closer to Solih’s MDP, which has skilfully crafted its image as a champion of liberal democratic values in a convoluted political landscape. On the other hand, both Maumoon and Yameen were seen with suspicion, whether due to their geopolitical positions or personal histories of corruption and, in the former’s case, alleged authoritarian tendencies.

In the meantime, however, much has changed in Malé and Brussels alike. Muizzu has broken ties with Yameen and emphasised his openness to future, non-military cooperation with other players. In Brussels, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen introduced the concept of a “geopolitical Commission”, pushing for a greater role by the EU outside of its traditional spheres of influence. Its flagship project in Asia and the Pacific is the Global Gateway initiative, designed as a competitor to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, albeit with more normative strings attached and a more limited scope than its Chinese counterpart.

It remains to be seen how much the Maldives’ foreign policy will evolve, given the nation’s strategic location in the Indian Ocean. Balancing ties with the West, India, and China will be crucial as the Maldives navigates its geopolitical position, with economic and security factors likely to weigh equally in Malé’s choices. As the recent diplomatic skirmishes with India demonstrate, even the most earnest shifts to pragmatism are ultimately constrained by the ideological pillars on which one’s political trajectory is founded. This, for better or worse, is as true in the elegantly decorated walls of Malé’s Muliaage Palace. In this former princely residence, Muizzu lives, as it is, in the modernist Belgian corridors of the European Institutions.

The author is a Brussels-based expert in Central and Eastern European affairs