The Chinese responded with dismay at this bizarre claim by the Americans, and relations between the two countries have failed to normalise since.

Shortly after the Great Balloon Scare of 2023, the Biden White House began talking about the dangers inherent in the deep linkages between the Chinese economy and the rest of the world. Commentators began to discuss whether America and its allies could decouple from the Chinese economy. As it became increasingly obvious that this was impossible due to the sheer scale of economic integration that globalisation has led to, American officials began to instead talk about “derisking”.

To this day, it remains unclear what derisking means. The meaning of decoupling is clear enough; it means that Western economies try to minimise trade and investment links with China. Derisking appears to mean something like onshoring components that are considered key from a national security perspective. Certainly, America’s attempt to restrict Chinese access to advanced semiconductor technology was justified on the basis that China might use these for military purposes.

Of course, this is all a matter of interpretation. In 2022, for example, China produced 7.5 times as much steel as the European Union and 12.6 times as much as the United States. In the case of serious military conflict, it seems highly likely that sourcing steel to engage in material production would be extremely important. Yet, when derisking is discussed, it is usually in reference to high-tech products. A cynic might say that derisking really means an attempt by America and its allies to maintain a technological edge over China.

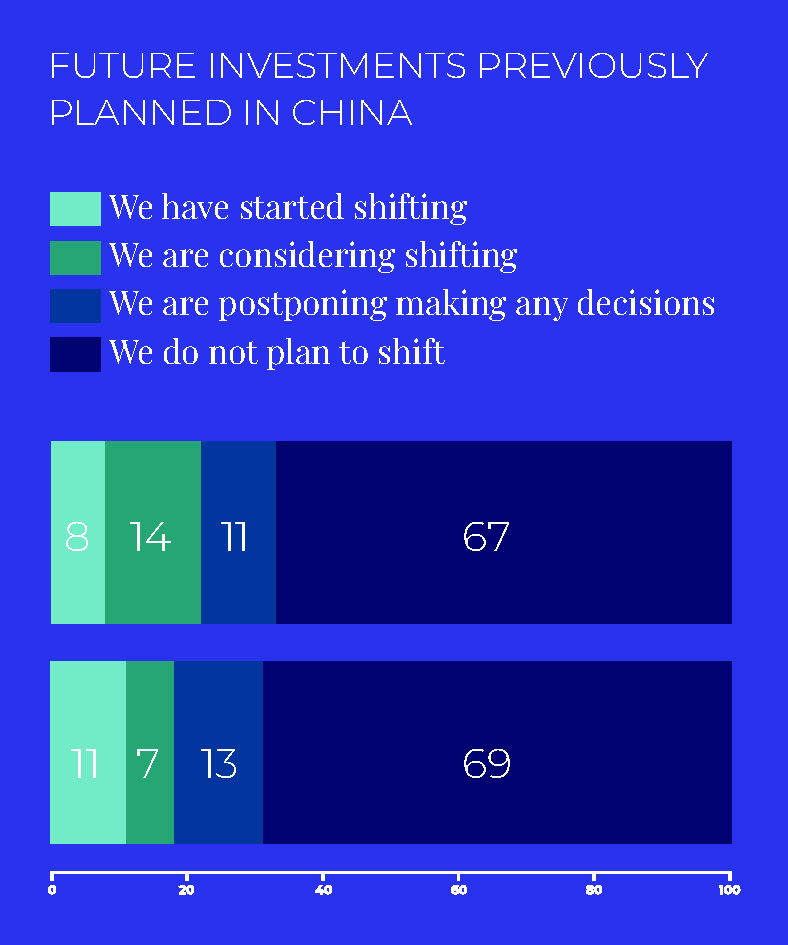

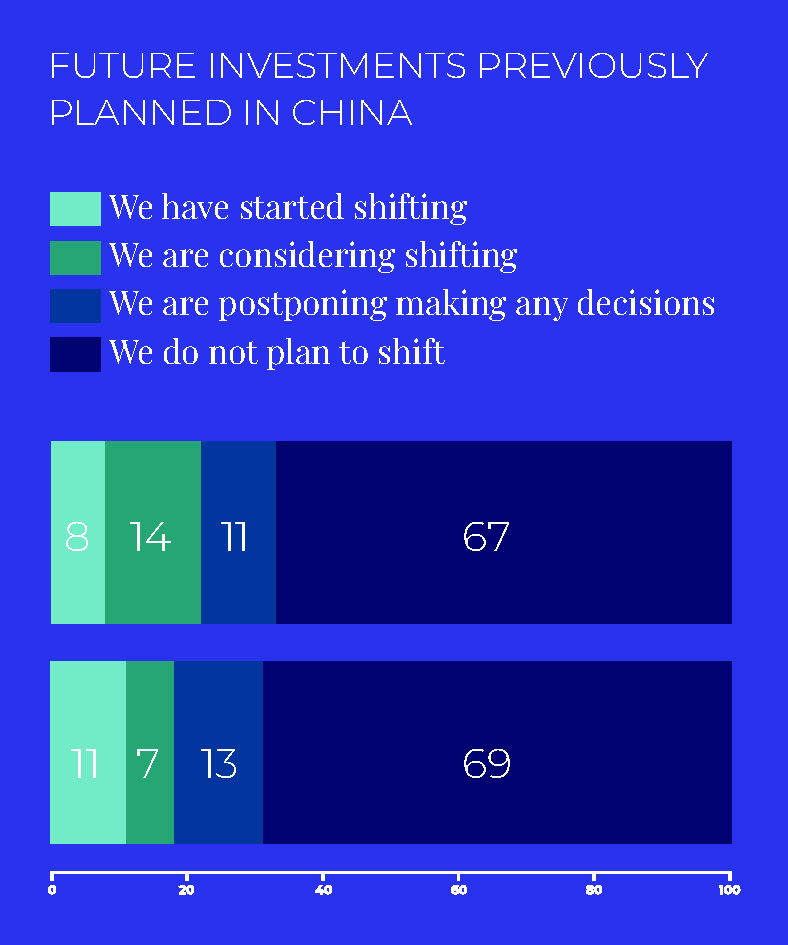

Only one in 10 European companies have shifted investment away from China, according to a recent survey by the European Chamber of Commerce in China, published in the Financial Times (FT). The vast majority of companies do not plan to shift. According to FT, “Apple and Intel have allocated future investments to other countries including India or south-east Asia while maintaining their China plants, in a hedging strategy known as ‘China plus one’. But the most contemplated strategy is ‘China for China’, whereby China operations are reorganised so that they produce goods only for domestic consumption.”

How has the American strategy been working so far? Not very well. In recent weeks, the Chinese company Huawei has released its new smartphone, the Mate 60. The new phone contains a domestically produced chipset, the Kirin 9000S, that the Americans thought the Chinese were incapable of producing.

After the Mate 60 was released, the Chinese government announced that they would be allocating a further 40 billion dollars to the so-called “Big Fund”, which invests in innovation in the Chinese chip industry. The American sanctions on China seem just to be forcing China to in-house chip production, thereby undermining the competitive advantage currently enjoyed by Western companies on the world stage.

Western companies seem completely baffled by the derisking rhetoric. This is not surprising because the messaging is extremely unclear. In the case of, say, the sanctions imposed on Russia, it is clear what Western companies can and cannot do. But the vagueness of the derisking rhetoric just leaves Western companies confused. A survey by The Financial Times shows that only 8 per cent of European companies claim that they have started shifting future investment away from China, with 14 per cent saying that they were considering it.

The data on foreign direct investment (FDI) shows some nervousness, too, having fallen by 34 per cent in September of this year. But all of this begs the question: who benefits from this? China is far too large and advanced an economy to rely on FDI in the same way a small country like Hungary does. If Western companies pull their operations out of China or even cease to grow them, it seems likely that the Chinese will just create their own. Whichever way you look, it appears that American-led attempts to legislate their competitiveness through diktat are self-defeating – something anyone who has taken an undergraduate class in economics should have been able to tell you.

The author is a macroeconomist, investment professional, and an external fellow at the Hungarian Institute of Foreign Affairs