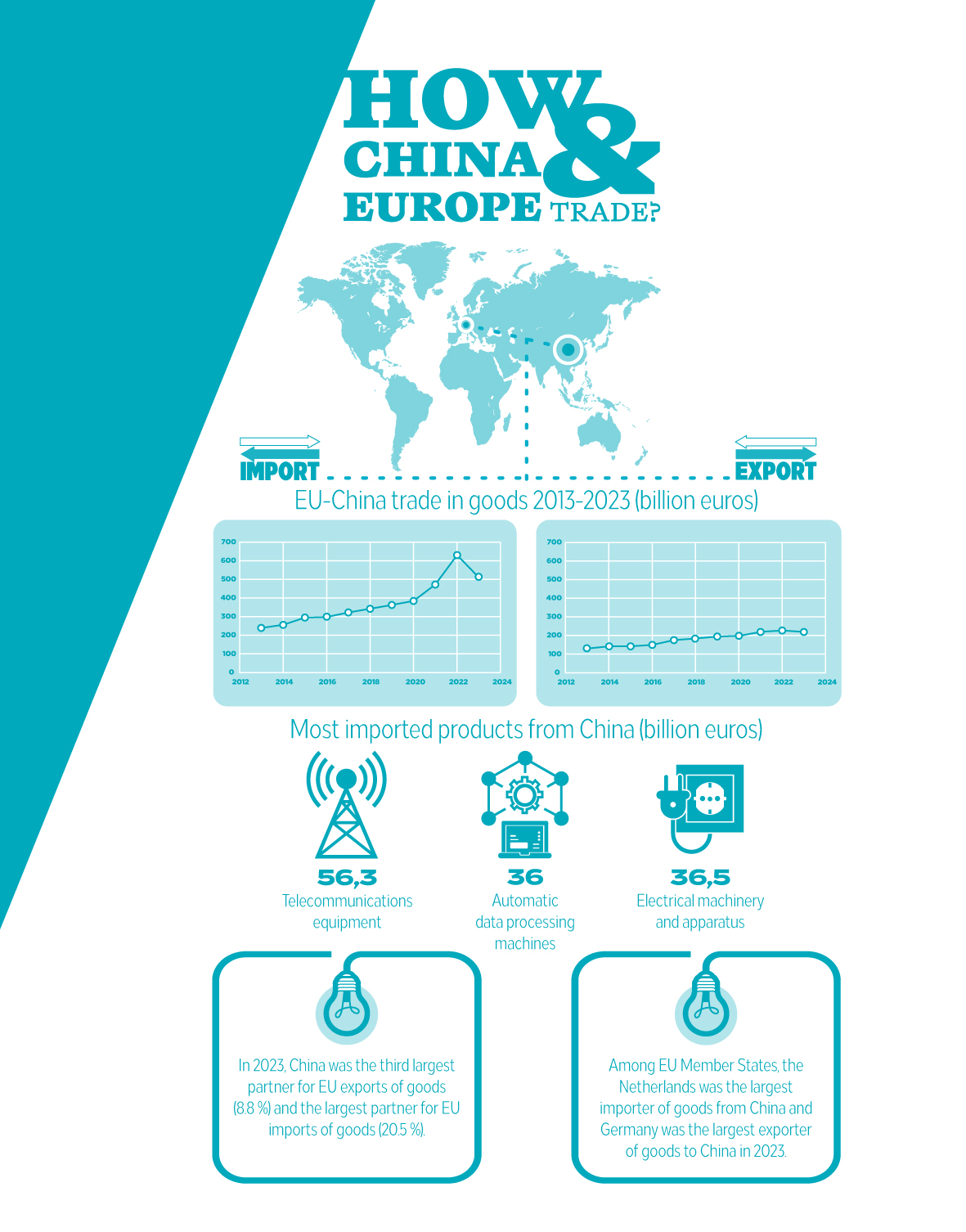

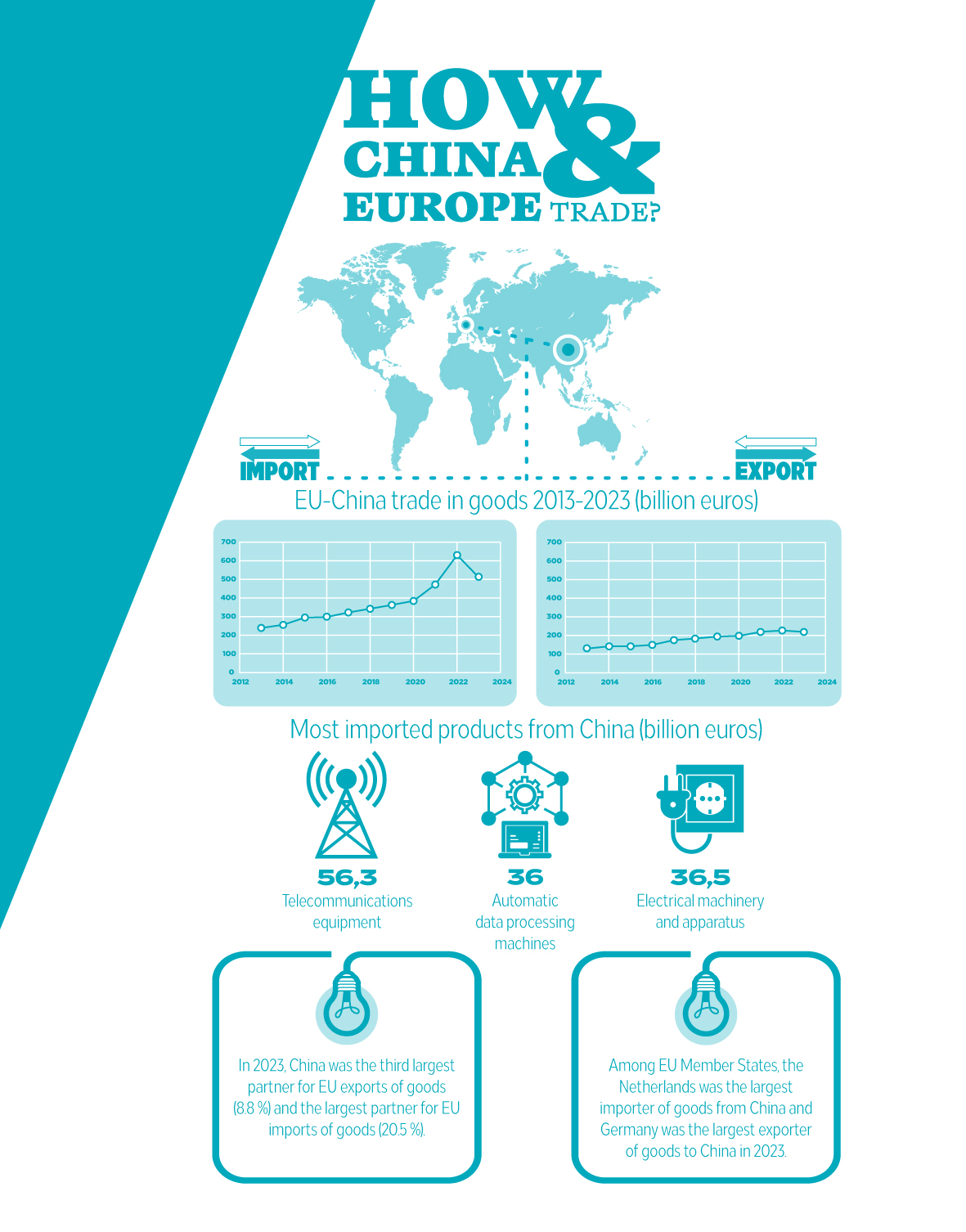

Energy-intensive German industry first wobbled badly in its move away from cheap Russian imports of raw materials. The companies that drive Europe's economic engine had not even recovered from the consequences of cutting off energy supplies when the next big challenge in German politics was to de-risk from China. In the government's view, a persistent trade deficit with China - 86.1 billion euros in 2022 and 58.4 billion euros in 2023 - threatens fair trade rules and thus the market and competitiveness of European companies.

Independence from China divides German firms into two camps. On the one hand, there are the Mittelstand, or medium-sized, usually family-owned businesses whose primary aim is to pass on from one generation to the next, rather than to maximise profits. They are focused on predictability and security, so they have already begun to market independence from China and to strengthen their supply chains after the coronavirus outbreak. Their strategy is therefore in line with the government's de-risking strategy.

By contrast, giants such as Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz and the BMW Group do not want to hear of any decoupling from the Asian country or any sanctions against Beijing, as there is too much at stake: in 2023, Volkswagen sold around 3.2 million cars in China, 35 percent of its total sales. For BMW, the figure is 825,000 (32 per cent), while for Mercedes-Benz it is 727,000 (29.5 per cent).

According to former German Environment Minister Norbert Röttgen, the move away from cheap Russian raw materials is in many ways a blunder, but if there were to be a conflict or counter-sanctions against China, the consequences for the country's industry would be disastrous. Ola Källenius, CEO of the Mercedes-Benz Group, has a similar view, arguing that protectionist measures by the European Union against China will also have a negative impact on the European economy.

The figures reflect the views of large companies. German direct investment in China rose by 4.3 percent year-on-year to a record high of 11.9 billion euros. Despite the announced policy direction, Germany has invested more in the Asian giant in the past three years than in the previous six years combined. While German regulation does not seem to follow national business needs at the moment, it could also be dangerous in the event of a Chinese backlash, with serious consequences for export indicators not only for Germany but for Europe as a whole.

The author is an analyst at the Makronóm Institute